The classic challenge of (profitably) serving SMEs for financial institutions

Many financial institutions continue to find it difficult to effectively and profitably serve the SME segment. While there are multiple reasons for this, the SME finance gap is primarily due to three interrelated costs that financial institutions face, which represent challenges inherent in serving SMEs:

Information costs: SMEs are incredibly heterogeneous with varying degrees of formality and are typically more opaque than larger corporations due to a lack of reliable and readily available financial information. This results in high information asymmetries for financial institutions, who cannot necessarily rely on formal financial statements, credit reports, or other documentation, making the cost of assessing credit risk significant. Many financial institutions resultantly rely heavily on collateral, which excludes many SMEs, particularly those with lighter balance sheets. This is a problem in Central Asia, where the value of collateral needed to obtain a loan for a SME varies from 170% of the loan amount in Tajikistan to 227% in Mongolia.[2]

Transaction costs: In addition to the challenge of information asymmetry, the relative transaction costs of serving SMEs may be higher than those involved in serving larger corporate clients or other clientele. This can be due to relatively fixed per-transaction or overhead costs spread over smaller ticket sizes, factors such as distance, (i.e., SMEs potentially being further from branches), a higher rejection rate of SME loans due to higher credit risk, etc.

Opportunity costs: Even if financial institutions identify the profit potential in a fitting SME lending approach, the actual profitability of serving SMEs in absolute terms may pale in comparison to serving larger corporate or retail clients, or, in some contexts, lending to state-affiliated enterprises. In contexts where capital or human resources are constraints, financial institutions may find the opportunity cost of focusing on SMEs too high. Put in simple terms, in almost all markets, SMEs are rarely the “low hanging fruit” for financial institutions.

Given the unique challenges in serving SMEs profitably, most successful SME finance providers have invested in a targeted approach, with SME-related finance as a dedicated segment or profit centre with SME-focused staff, products, and procedures—but this typically requires significant investment and commitment. As a result, any strategy, approach, or technology that can successfully reduce the costs above (without costing too much itself), or mitigate the risks of lending to SMEs, can play a role in facilitating SME finance and enabling financial institutions to more profitably target the SME segment.

The purpose of this paper is to show how a value chain-focused approach, which includes understanding value chains and the position of SMEs in those value chains—often in relation to larger anchor businesses—can enable financial institutions to expand SME finance outreach and profitability.

No business is an island: what are value chains?

But first, what exactly is a value chain?

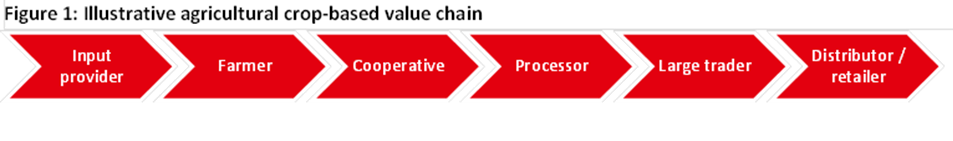

A value chain can be defined as the full range of activities and players that are required to create, produce, and deliver a product or service. In fact, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO), all products and services are part of a value chain, whether global or local.[3]

The term value chain is often used interchangeably with the term supply chain, which historically has a stronger focus on operational aspects for businesses: procurement, production, and logistics. The term value chain, on the other hand, was coined by renowned business author Michael Porter in 1985 and focuses more on the series of activities that adds value to a product or service at each step, ultimately transforming it to a final good or service. While traditionally value chain analysis focused on the value added by a single business (or business unit) to a good, the value chain concept is used broadly today to consider entire sectors (e.g., coffee or shoe production).

The term value chain is often, though by no means exclusively, used in an agricultural context, highlighting the process, players, and value added to bring agricultural goods from farms to consumers. The term is equally useful in other contexts or sectors, however, particularly where goods are processed or produced, from the complex with a multiplicity of actors and activity levels (e.g., airplanes or mobile phones) to the more basic (e.g., food or small commodities).

Regardless of the terminology used, all financial institutions naturally recognise that the majority of their business clients—including SMEs—are part of business chains with an upstream (suppliers) and a downstream (buyers/customers), and that the success of their business clients (and the financial institution’s credit risk) is heavily influenced by this chain. The value chain perspective is helpful for better understanding relationships between value chain actors, as well as the sequence of all relevant activities along the chain.

While value chains may be domestic or global—that is, stretching across multiple countries—most SMEs in Central Asia are focused on the domestic market, and thus the discussion in this paper focuses on domestic value chains.

Value chain finance for financial institutions

A key feature of several value chains is the presence of a major or anchor business. Such a business is typically a larger corporation, potentially affiliated with a multinational, that has a relatively dispersed “upstream”—i.e., multiple SME suppliers—or a dispersed downstream—i.e., multiple SME retailers or vendor businesses. Depending on the position of the anchor business (e.g., up or downstream), anchor-driven value chains are often referred to as buyer-driven or producer-driven chains.

While much analysis typically focuses on the good(s) being produced by a value chain, a helpful view of value chains focuses on value chains as a series of linkages involving regular and predictable exchanges between players (particularly around anchors) of the following:

- Goods and services – flowing downstream, ultimately to the consumer

- Finance and funds – flowing upstream to producers and suppliers

- Information – flowing both ways, though not always recorded or consolidated

Very few value chains are characterised by the immediate settlement of transactions, and thus credit is a natural and critical component of almost all value chains. Value chain players, particularly anchor businesses, often extend forms of credit, including even longer-term financing, which may sometimes be delivered or repaid in kind.

Table 1 shows information on the percentage of firms using banks and supplier/customer credit to finance working capital in four Central Asian countries—all below the global average.

Table 1: Key Central Asian indicators

|

|

Kazakhstan |

Kyrgyzstan |

Tajikistan |

Uzbekistan |

All countries |

|

% firms with a bank loan/line of credit |

17.2% |

25.8% |

18.0% |

22.2% |

33.1% |

|

% firms using banks to finance working capital |

13.2% |

18.8% |

12.8% |

23.7% |

30.0% |

|

% firms using supplier/customer credit to finance working capital |

20.7% |

6.4% |

12.4% |

2.9% |

29.5% |

Source: World Bank Enterprise Surveys[4]

The presence of flows of goods, funds, and information between actors creates a value chain finance (VCF) opportunity for financial institutions.

Good-practice MSME credit analysis and underwriting approaches at financial institutions focus on the individual SME business in question, understanding the ability and willingness of the business to repay. In this way, this approach tends to view each SME as an independent entity, and an exhaustive analysis of the SME’s upstream or downstream usually only occurs if the SME is particularly reliant on a specific supplier/buyer or contract, i.e., there is potential concentration risk.

VCF instead takes a holistic approach, seeking to understand the overall structure and nature of the value chain, identifying suboptimal elements of the chain in terms of finance provision, particularly liquidity gaps, and then identifying opportunities to provide profitable financial products and services to businesses within that value chain.

Effective VCF approaches typically focus on relatively integrated and stable value chains, and often centre around an anchor business or businesses—often existing clients of the financial institution—and seek to leverage the position of the anchor to mitigate risk and provide financial services to suppliers or buyers.

Anchors often already engage in the provision of finance to value chain actors themselves as a means of ensuring stable supply or timely delivery, developing loyalty, or promoting sales. “Outsourcing” this financing to a specialised financial institution can be attractive to anchor businesses for a variety of reasons, including freeing up working capital and improving liquidity, reducing administrative and transaction costs, de-risking the balance sheet, simplifying collection, receiving commission income, etc.

Additionally, although value chains are often graphically displayed in a linear fashion, it can be helpful to think of a wider web or ecosystem of indirect chain actors, including equipment suppliers, logistics providers, information services, employees, regulatory bodies etc. As such, by focusing on the ecosystem as whole, financial institutions can leverage existing clientele and their extended networks to more effectively reach new clients and cross-sell products (e.g., payment transactions, payroll services, letters of credit etc.).

The value of collaboration: partnerships with value chain players

Typically in VCF some form of strategic alliance is established between a financial institution and one or more value chain actors—typically the anchor—to reduce transaction costs and lower risks that otherwise impede access to traditional financial services.

Typically, through a partnership, the anchor may offer the following to financial institutions:

- Information: The anchor can provide critical information on upstream or downstream SME (and other) actors in the value chain, including the provision of referrals or introductions, borrower screening, transactional data, sector-specific data, contract or document verification (e.g., purchase orders or invoices), credit need information, etc. Such information may assist financial institutions in identifying or assessing potential clients, allowing them to “outsource” elements of credit assessment.

- Transaction facilitation: The anchor can more directly support the facilitation of financial transactions, whether through directly supporting loan disbursements, co-signing, establishing reverse factoring schemes etc.

- Guarantees: The anchor may provide guarantees or engage in other risk-sharing mechanisms (e.g., co-signing, buyback schemes) to mitigate credit risk and indirectly facilitate transactions with SMEs for financial institutions.

From the anchor’s perspective, formal or informal partnership with a financial institution may facilitate either procurement or sales/distribution.[5] For the financial institution, such collaboration allows for the reduction of information asymmetries and transaction costs, as well as the expansion of service. The specific nature and depth of partnership with the anchor(s) must be defined on a case-by-case basis by the financial institution based on its analysis of the value chain and negotiations with the anchor.

Potential risks in value chain finance

Engaging in value chain finance presents potential risks and challenges for financial institutions as well that must also be considered, perhaps the most obvious of which is the concentration risk resulting from having a significant amount of exposure related to a single value chain or anchor company.

As SMEs supported through VCF approaches are likely part of the same value chain(s), covariate risk may be a serious issue, with external or other influences negatively affecting multiple businesses simultaneously.

Systemic risk is also a challenge, with the possibility of idiosyncratic risk at one value chain player (particularly the anchor) rippling up or down the value chain, creating a literal “chain reaction”. As a result, linked businesses may suffer, again creating potential covariate risk, particularly in strongly linked value chains.

As a result, a careful analysis of the value chain is critical, and a deep understanding of the linkages between businesses in the value chain is required.

Financial institutions should also carefully consider and establish concentration or exposure limits to value chains and sectors to mitigate such risks, as well as ensuring strong monitoring and risk control systems over time.

Anchoring the approach: developing value chain finance at a financial institution

So what can a financial institution do to effectively establish a VCF approach?

Successfully utilising VCF approaches requires a clear understanding of the nature and risks in a value chain as a whole, and the identification and assessment of a fitting anchor business with whom to collaborate. This is a move away from assessing the credit risk of each individual SME borrower, typically resulting in higher upfront costs for financial institutions, but, if done correctly, with the potential to scale those costs over many clients and achieve economies of scale with reduced individual transaction costs.

The following are potential steps for financial institutions to get started:

1) Identify potential anchors and their value chains: Assuming that a financial institution has already engaged in corporate and/or SME lending in a market, it is often beneficial to start by identifying the value chains in which existing financial institution clients—particularly potential anchors—are participating. As a first step, larger or more significant corporate clients may be identified, considering the depth, longevity, and nature of the business relationship between the financial institution and the potential anchor.

From this initial scan, a “shortlist” of potential value chains and anchors may be established. A thorough due diligence of a potential anchor business should be conducted (or previous analyses updated), with the goal of not only understanding the anchor itself but the value chain in which it participates. As VCF approaches typically involve a formal or informal partnership with the anchor company, at this stage aspects of reputational risk in partnering with an anchor should already be considered, as well as the anchor’s potential willingness or interest in collaboration.

A benefit from using existing clients/sectors as a starting point is that the financial institution or financial institution staff may have existing knowledge and/or expertise in the relevant sector.

2) Map the target value chain: The presence of a strong potential anchor business does not necessarily indicate an ideal target value chain. As much as possible, financial institutions should focus on value chains demonstrating strong integration and higher levels of liquidity. The more linked a value chain is, the more reliable are the flows of goods, services, liquidity, and information between the players and, all things equal, the lower the default risk of a particular business within the value chain.

Financial institutions should thus “map” value chains, identifying the anchor(s) and players, the links between them (and the strengths of those links), and potential weaknesses. During this step, the financial institution should take care to confirm that the potential anchor business identified in the first step actually is indeed the prominent company in the value chain, demonstrating strong negotiating power with SME suppliers and buyers.

Quantitative and qualitative criteria regarding the value chain should also be considered, including: the recent development of and structural changes in the sector/industry, production volatility, price volatility, reliance on domestic/foreign markets, volatility of financial flows, policy issues/risks, formality of relationships, negotiating power, etc.

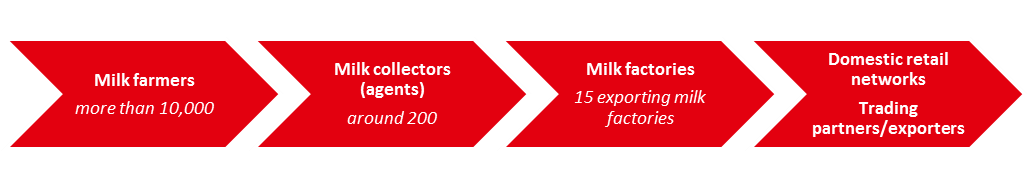

Box 1: The dairy value chain in the Kyrgyz Republic[6]

|

Value chains naturally vary, with each Central Asian country have its own dominant domestic sectors and prevalent value chains. Taking the Kyrgyz Republic as an example, a key value chain is the dairy value chain, which provides milk both for domestic consumption and export.

The majority of fresh milk in the Kyrgyz Republic (70%) is traded by smallholder family farms in the form of fresh milk. Although annual milk production is 1.5 million tons, only 8-10% of milk is processed by milk factories. In the dairy value chain, milk factories (15 of which are permitted to supply milk to the EEU) are potential anchor businesses, typically buying milk from upstream milk collectors (agents) and selling through domestic retail networks or trading partners/exporters. Kazakhstan and Russia are major export markets for processed milk and dairy products (butter, cheese, yogurt, ice cream). Both milk farmers and collectors seek better access to finance and improved interest rates, with milk farmers often covering a significant portion of their operating costs through finance if possible. Value chain finance approaches may allow partnership opportunities with milk factories to improve financing to milk farmers and milk collectors in the Kyrgyz Republic. |

Based on this, the financial institution should develop a clear understanding of how each player in the value chain adds value, as well as a detailed understanding as to the current financial needs and practices of the players.

3) Identify business opportunities: Based on the mapping and understanding of the value chain, and potentially in coordination with the anchor business, the financial institution can identify potential entry points and business opportunities in the value chain.

Such opportunities may often be based around shorter-term liquidity needs or gaps, but may also involve longer-term asset financing opportunities. Additionally, financial institutions may attempt to identify opportunities to cross-sell or offer a suite of products to value chain players.

Common VCF instruments include:

- Short- and medium-term credit (e.g., lines of credit)

- Equipment leasing

- Medium- and longer-term credit (e.g., vendor financing for equipment purchases)

- Current accounts and transactional services (e.g., payroll, POS)

- Receivables financing (e.g., factoring, bill discounting, forfaiting, reverse factoring)

- Collateralised financing (e.g., repo financing, warehouse receipt financing, inventory financing)

- Letters of credit and letters of guarantee

- Insurance

- Derivatives (futures, forwards, options, swaps)

During this step, formal cooperation with the anchor company may also be defined and negotiated. What service (if any) will the anchor provide (e.g., data, guarantees, referrals), and what will the anchor receive in exchange for this (e.g., commissions, discounts, branding, etc.)?

4) Set targets and concentration limits: The financial institution should set risk parameters (portfolio limits), as well as define a risk monitoring approach to ensure that these limits are adhered to at the portfolio level. At the same time, targets should be set to spur financial institution staff to achieve economies of scale and take advantage of the value chain opportunity.

5) Implement and adapt over time: Ideally, while the financial institution may wish to pilot the approach within a single or small number of value chains, a larger number of value chains (and anchor businesses) are considered in order to diversify and ensure limited exposure to a single sector or value chain. Attempts should also be made to explore additional ways to reach the ecosystem surrounding the value chain as possible.

Value chain finance in the digital age[7]

While VCF approaches and concepts are hardly new, the emergence of new digital tools and technologies, including the recent explosion of data availability and data processing capabilities, has created new opportunities for innovative financial institutions to explore VCF schemes. The potential value of such digital VCF approaches has only increased with the acceleration of digitisation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic globally.

Supply chain digitisation promoting transparency and data availability

The increasing usage of digital tools and digitised interactions within value chains has made data regarding physical and financial transactions more available and transparent. Activities previously conducted physically (e.g., by paper, in cash, in person) are increasingly recorded or monitored digitally at each stage: contract signing, ordering, tracking goods, delivery, sales, payments, etc. As a result, data regarding the frequency of purchases or sales, interactions with suppliers and customers, and inventory turnover are now more available, allowing for increasingly tailored and automated credit risk assessments and decisions by financial institutions. This data availability may alleviate the need for an anchor to provide detailed information, or supplement the information provided by an anchor.

Transformational impact of platforms

The increased use of a variety of digital platforms has created opportunities for VCF approaches with value chains that might have been seen as relatively fragmented or small-scale in the past. As transactions are increasingly facilitated by digital platforms that further track and consolidate information, financial institutions can particularly consider platforms as partners in aggregating value chain players and collecting the information necessary for providing value chain finance. Partnering with digital platforms can allow financial institutions to receive detailed, and in some cases real-time, transaction data and other relevant information. Examples of platforms include e-commerce platforms such as Alibaba or Amazon, national e-invoicing hubs, fintech-provided platforms, etc.

Opportunities remain to be ahead of the curve in many markets

Digital financing based on digital transactions throughout value chains is already increasingly prevalent in many countries around the globe, but many opportunities remain, particularly in emerging markets—such as those in Central Asia—and in value chains that are presently more fragmented (e.g., multiple smaller-scale producers and buyers, fewer repeated transactions). The increasing availability of data can reduce information and transaction costs for financial institutions, allowing such institutions to provide finance more efficiently, further incentivising shifts towards digital approaches and the digital integration of value chain players.

The new opportunities brought about by digital disruption for financial institutions are coupled with new challenges. Potential collaborators (e.g., fintechs, platforms) may also be competitors in the provision of VCF as barriers to entry (e.g., informational costs, transaction costs) have been reduced by the presence of technology.

[1] MSME Finance Gap: Assessment of the Shortfalls and Opportunities in Financing Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Emerging Markets. International Finance Corporation (IFC), 2017. (https://www.smefinanceforum.org/sites/default/files/Data%20Sites%20downloads/SME%20Report.pdf)

[2] As quoted in OECD 2017 “Enhancing Competitiveness in Central Asia” (p 47). (https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264288133-5-en.pdf?expires=1607683633&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=6128AC11281F3DAC0F5F5747CE96872F)

[3] A Rough Guide to Value Chain Development: How to create employment and improve working conditions in targeted sectors (ILO), 2015, 2.

[4] www.enterprisesurveys.org. Accessed on 16.12.2020.

[5] A classic “win-win-win” value chain finance example is when a financial institution lends to a (SME) producer based on a contract with its (anchor) buyer, replacing the need for the anchor to provide credit. This frees up working capital at the anchor, facilitates credit for the producer (perhaps on better terms), and allows the financial institution to lend to a new SME client with reduced transaction costs.

[6] The content of this box was adapted from: ADBI Working Paper Series, Leveraging SME Finance Through Value Chains in the CAREC Landlocked Economies: The Case of the Kyrgyz Republic, Kanat Tilekeyev, (ADBI, No. 972), 2019.

[7] This discussion has been heavily influenced by: Technology and Digitization in Supply Chain Finance (IFC), 2020.

The whole world is feeling the impact of the crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Many economic sectors have been hit, resulting in negative economic consequences. Against the background of the pandemic, the Central Asia regional economy is forecast to contract by 1.7 percent in 2020. Experts of the World Bank state that the Central Asian region is experiencing an economic downturn not seen since 1995.[1] According to surveys by national chambers of commerce and business associations, 60% to 80% of companies in most of Central Asia have been severely affected by the coronavirus crisis.[2] Businesses are losing revenue, shops are closing, and supply chains are disrupted.

The crisis is undermining the income and liquidity levels of individuals and legal entities, including micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), as well as their ability to meet obligations to financial (credit) institutions. At the same time, everyone understands that without financial support, businesses will not be able to recover to pre-crisis levels for a long time. But, how can we, under such conditions, build relationships with clients, what and how should we evaluate their situation and outlook, and how can we make lending decisions and/or decisions on changing current loan payments, so that clients can survive the crisis and repay their loans in a way acceptable to financial institutions? In this article, we will give recommendations on what to look for when analyzing businesses during times of crisis.

In general business assessment is aimed at identifying potential trends and negative consequences for business development. At the same time, a high-quality assessment of the financial condition of a business gains more relevance during times of crisis, i.e. in unstable environments. We should keep our finger on the pulse of those enterprises that have already received a loan and now have to service their debt. We should also be able to analyse the businesses of new clients and assess their lending capacity in order to support them and the economy as a whole in overcoming the crisis.

Nowadays, many enterprises and sole proprietors find themselves in a difficult financial situation (temporary insolvency or even bankruptcy), and the task of an analyst is to determine the best support measures for a given client in the current situation. Such support measures could include changing the terms of an outstanding loan or, perhaps, providing additional finance.

During a crisis, business analysis involves objective assessment of a business’ financial condition, plans and development prospects, including its ability to adapt to the current and expected economic situation and trends.

In the process of decision-making about the possibility of cooperation with potential clients and/or support of existing clients, financial institutions take an integrated approach to the analysis (including analysis of market data and macroeconomic indicators, of formal and managerial financial statements, as well as retrospective and prospective business analysis). It is very important to look not only at numbers, but also to understand business processes and the (owner’s, management’s) current and future response to the crisis.

Shops may see declines in sales, manufacturers my see a drop in production output and sales, or the entire production process may come to a standstill because of a lockdown. There is an overall slowdown in profit-making business activities. At the same time, most business costs remain on the same level, and the financial balance in a business is disrupted, which translates into a decrease in financial stability of the business.

In a crisis, some people are prone to panic and to make irrational choices, other people “freeze in denial”, refuse to admit that the situation has changed and continue to live and work as if nothing has happened in the hope that things will resolve themselves on their own. Others, will analyze the situation and look at their business and circumstances as an opportunity for survival, think about possible measures to make the most of the changing environment. They may try to cut costs, find new sources of liquidity and income (for example, switch to a different, more reliable line of business and some may already have a contingency plan in place).

Here are some negative implications for a business that an analyst can observe in the process of analysis:

- decreasing revenues

- decreasing margins of individual business units (sales points, divisions)

- decreasing profits (or even losses)

- reduced liquidity (or lack of liquidity)

- delays in supplies and/or changes in supply chains

- disruption of supply chains

- termination of relations with suppliers

- an increase in accounts payable (to suppliers and creditors). Incurring private debts during such periods can be especially worrisome

- an increase in accounts receivable (customers stop paying on time)

- a decrease in working capital

- lack of finance

- loss of clients

- cancellation (failure) of contract obligations

- etc.

This list is not exhaustive. These negative consequences can even lead to business closure. However, let us look at the problem from a different perspective. In times of crisis, businesses need to be especially flexible, try to adapt to the new conditions, choose the right strategy that could help the business to overcome the crisis. For example, this could mean:

- reducing investment projects

- closing unprofitable production / points of sale

- selling non-core assets

- optimizing costs (especially, fixed costs such as rent, salaries, advertising, transport and other expenses)

- revising the assortment of goods

- entering new markets

- switching to online modes of conducting business

- changing settlement schemes with suppliers and buyers (reduction of payments, barter, etc.)

- making use of all available government support measures and tax opportunities to optimize spending

- etc.

The above-mentioned crisis phenomena and measures to overcome them serve as a hint for financial organizations on what to pay attention to in the process of risk analysis and assessment. However, attention should be focused not so much on the problems as such but on their depth and the tactical and strategic measures taken by the business (owners) to overcome the situation.

In order to find a way out of the crisis, business owners and their teams (depending on the size of the business) explore opportunities, analyse their own business, the market and general economic trends, and they take action. Our task, as analysts, is to recognize measures that are focused on overcoming the impacts of the crisis, to evaluate them and draw conclusions. If a company is "in panic" and does not take any measures, then we must clearly understand that financing it is associated with a high risk. If a business takes active and meaningful actions as a reaction to the current circumstances, looks out for options to adapt to the situation and has a real perspective for the future, then financing such a business is associated with fewer and lower risks. Thus, apart from current financial indicators, the first thing to pay attention to during the analysis is the owners’ (management’s) own reaction, how they assess the situation, how they plan to get out of it, and how this will affect their business productivity and financial performance. A business can still be profitable and have good credit capacity at this time, but the owners’ (management’s) actions/ omissions can lead to a situation where the business may become unable to pay in a matter of weeks or months. Therefore, it is important to see how effective and rational the owners’ plan is, and whether it is focused on business growth and development, even in a difficult period.

What business periods should financial institutions consider and what should they focus on in their analysis?

Analysing past periods. What is the point of this? The purpose of analysing business development over periods preceding the crisis is to understand how much the situation has changed and evaluate the steps taken by the owners. If a business shows a dramatic decline in revenues, profits, has liquidity gaps and/or other negative trends, the probability is high that owners so far have not taken any action or only insufficient action. In this case, it is high-risk for a financial institution to finance/work with such a business, since the owners (management) are likely to continue with their wait-and-see attitude in the hope that the situation will resolve itself on its own.

If you analyse a business that has already survived economic crises in the past, you should look at how they managed this. It is not necessary to delve into accounting records, but sufficient to talk with the owners (management) and find out whether they had to reduce or optimize their business or not, how they got out of the situation back then, and compare this with the current circumstances.

Analysis of the current situation. Get answers to the following questions:

- Can the business cope with the current debt burden? How long will it be able to serve its current debts? From where does the business get the necessary resources? Why is it asking for more finance?

- To what extent is the client now dependent on borrowings?

- Given the current state of affairs, will the client be able to cope with an additional debt burden?

If a business needs a loan only to stay afloat, and you see that it is “frozen in a waiting loop” and/or there are signs of possible negative future trends, then financing such a business will bear high risks. You should always make sure that additional financing will not further aggravate the situation of the business.

Under conditions of uncertainty, the analysis of business prospects should be focused on the current situation and on the client's plans to overcome the crisis. The analysis involves an assessment of the client's plans against the background of general economic trends in the client's market and the economy as a whole, as well as the assessment of the relevance of the client’s plans against these trends (including the likelihood of meeting planned sales targets, income and expenses). If, in the process of your analysis, you see that the client has reconfigured business processes, abandoned ineffective projects, focused on products that are relevant and in demand in the current situation, and has a vision for future business development (at least, for some time horizon), skilfully manages his/her debtors (at least, works with them), tries to maintain acceptable liquidity and own working capital levels, then working with such a client will be less risky.

Therefore, when analysing a business in times of crisis, it is important to assess the business’ tactical, short-term measures, as well as its strategy to keep the situation under control and overcome the crisis. It is also necessary to analyse the core financial indicators (current and expected) which we use to assess business performance under normal conditions. These indicators include:

- balance sheet indicators such as equity, receivables and payables, working capital structure

- trends in the revenue structure, profitability and profit

- business liquidity and safety margin.

Analyse the firm's financial statements and collect managerial accounting data.

Look at the sources of financing that the business uses (owner’s equity, long-term or short-term loans). Having studied the structure of liabilities, you will be able to understand possible causes of financial instability of the business. This could be a high share of debts in the balance sheet total (more than half), which could mean that the business is highly dependent on its creditors.

Pay attention to the speed of growth of accounts receivable and payable, as well as their ratios. Their growth rates should be approximately the same.

Examine financial statements for any losses in the analysed period. You could notice changes in mark-ups, past due loans, receivables and payables.

Assess the liquidity and profitability levels of the business in the short and medium term. In a crisis, it is quite difficult to carry out medium-term cash flow projection and assessment of profit levels. Nevertheless, you can forecast cash flow and profit for the coming months, as well as build positive and negative scenarios (in case of stabilization and/or worsening of the situation). In any case, during situations of crisis and uncertainty, loan officers of financial institutions must conduct regular monitoring of their clients (the frequency of such monitoring is usually higher than in a stable environment). The purpose of monitoring is to check and assess the accuracy of cash flow and profitability forecasts. Monitoring allows loans officers to respond to any changes in the situation in a timely manner and adjust financial forecasts, payment plans and other credit conditions as necessary.

In the current conditions, financial institutions should adjust their conclusions and assessments to the crisis. If you see that a business is flexible and ready to not only manoeuvre with financial resources, but can also skilfully adapt its business processes and schemes, and optimize its activities, thus ensuring financial stability, then you can analyse such a business, evaluate data and take informed decisions with acceptable risk for the financial institution. You may not necessarily encounter super-profits in the process of analysis, but you can evaluate the scale of the changes and measures taken by the business to overcome the crisis and period of uncertainty, and assess the prospects of this business for the future. And this is the basis for finding the best way to support clients in crisis and post-crisis conditions.

[1] World Bank. 2020. “COVID-19 and Human Capital” Europe and Central Asia Economic Update (Fall), accessible by the link https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34518

According to the estimates of the World Bank experts, with an optimistic outlook, “the economic growth in Central Asia is expected to recover to 3.1 percent in 2021, supported by a modest rise in commodity prices and foreign direct investment. In the downside scenario for 2021, weaker-than-expected external demand, commodity prices, or remittances could dampen the recovery to 1.5 percent.”

[2] OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19).COVID-19 crisis response in Central Asia, Updated 16 November 2020, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-crisis-response-in-central-asia-5305f172/

Pictures designed by Freepik