Introduction

Vendor finance schemes provide an opportunity for financial institutions to deliver a unique product offering and to be more competitive in the SME financing market through the establishment of formal cooperation with equipment vendors looking to increase revenue.

SMEs typically acquire relevant productive assets (e.g., machinery or equipment) using one of three methods:

- funding from their own resources (e.g., company liquidity)

- financing from the equipment vendor

- financing received from a financial institution

Each of these methods has advantages and disadvantages for each party. However, the cost-benefit analysis for each party may be significantly adapted and made more desirable through the establishment of formal co-operation between financial institutions and vendors - so called “vendor finance schemes”.

Although a variety of vendor finance schemes exist, this document describes in detail two categories of schemes in which a financial institution and vendor formally co-operate: vendor subsidy schemes and buyback schemes.

In order to first provide a theoretical foundation, the document starts by describing the two traditional asset financing approaches (i.e., asset financing from the vendor or from a financial institution), highlighting the costs and benefits of these two approaches.

Following this, the benefits and drawbacks of the two vendor finance schemes (i.e., vendor subsidy schemes and buyback schemes) are detailed and compared with traditional financing approaches. Key considerations for the successful implementation of the vendor finance schemes are also highlighted.

Traditional asset finance approaches

In cases where SMEs (“buyers”) require finance to purchase new machinery or equipment, asset finance is typically supplied by equipment suppliers (“vendors”) or financial institutions (“FIs”).

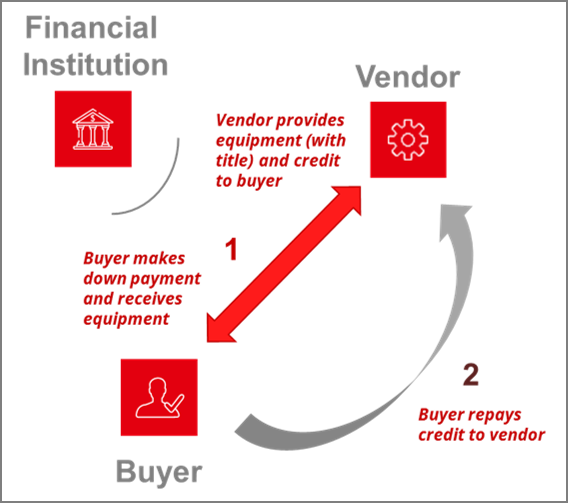

Asset financing from the vendor

While vendors of equipment naturally prefer receiving cash upfront for their sales, bigger-ticket equipment or machinery often represents a significant investment on the part of the buyer. The acquisition of such equipment may be a challenge for the liquidity of the buyer—sometimes resulting in lost sales for the vendor if the buyer cannot afford the equipment upfront and does not have financing options.

While vendors of equipment naturally prefer receiving cash upfront for their sales, bigger-ticket equipment or machinery often represents a significant investment on the part of the buyer. The acquisition of such equipment may be a challenge for the liquidity of the buyer—sometimes resulting in lost sales for the vendor if the buyer cannot afford the equipment upfront and does not have financing options.

As a result, in the traditional vendor asset finance approach, the buyer is offered credit by the vendor, sometimes after paying a certain percentage of the transaction amount as a down payment. The amount and terms of this credit may vary significantly, depending on the vendor, the nature of the client, the liquidity situations of both, previous business between the two, etc. In many markets, vendor financing may be referred to as “commodity credit” and may be very standardised or limited.

Given that vendors are typically more focused on sales rather than on financing, vendors often face challenges in managing credit portfolios of any significant scale. Additionally, the loss of an upfront cash payment from buyers may result in liquidity issues for vendors if done on a large scale. Therefore, many technology/equipment vendors find this vendor financing approach challenging or risky to employ on a significant scale, particularly those selling larger ticket technologies or equipment. As a result, many buyers may not have access to the type of financing they would need or prefer.

This financing approach does not (necessarily) involve a financial institution and has several advantages and disadvantages for both vendor and buyer.

|

PROS |

CONS |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Vendor |

|

|

|

Buyer |

|

|

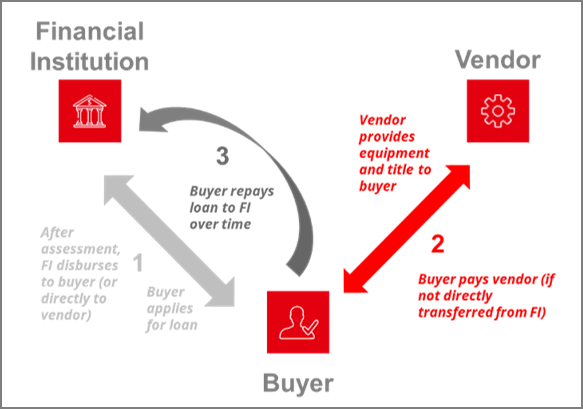

Asset financing from a financial institution

Many SMEs seek asset financing from financial institutions (FIs) to acquire needed equipment. In the traditional FI financing approach, FIs provide finance to buyers to acquire equipment, with funds often disbursed directly to the vendor.

Many SMEs seek asset financing from financial institutions (FIs) to acquire needed equipment. In the traditional FI financing approach, FIs provide finance to buyers to acquire equipment, with funds often disbursed directly to the vendor.

FIs typically conduct a credit analysis of the buyer’s business and take the acquired asset (equipment) as collateral for the loan. A key characteristic of the traditional FI financing approach is the lack of strong cooperation between the FI and vendor.

As FIs are in the “business of credit”, they are well positioned to provide necessary finance to buyers. However, receiving financing from FIs may take some time, and FIs may be hesitant to take equipment as collateral due to difficulties in assessing resale value (and a limited ability to resell such equipment).

|

PROS |

CONS |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Vendor |

|

|

|

FI |

|

|

|

Buyer |

|

|

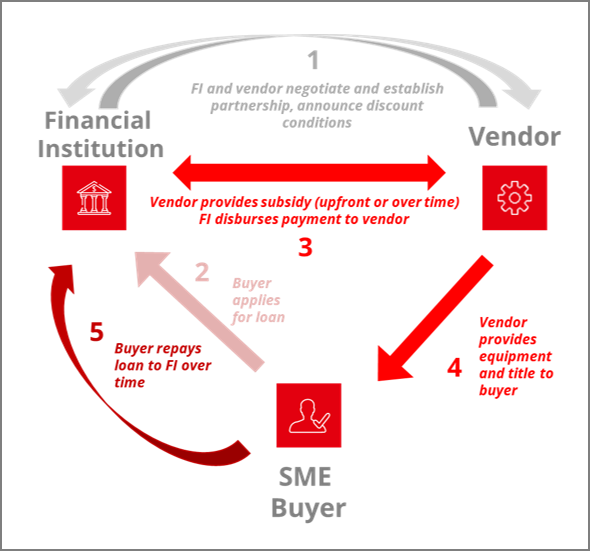

Vendor finance approach #1: vendor subsidy schemes

Overview

In order to boost sales of certain equipment, the vendor agrees to pay a subsidy to the FI, thus discounting the cost of lending and enabling the FI to offer preferential financing conditions to buyers seeking to purchase selected equipment and machinery from the vendor (e.g., the FI offers an interest-free or lower interest rate loan).

In order to boost sales of certain equipment, the vendor agrees to pay a subsidy to the FI, thus discounting the cost of lending and enabling the FI to offer preferential financing conditions to buyers seeking to purchase selected equipment and machinery from the vendor (e.g., the FI offers an interest-free or lower interest rate loan).

The subsidy provided by the vendor may be in the form of an upfront discount to the FI, or paid over time as an interest rate subsidy (i.e., paid as the SME buyer repays).

From another perspective, the vendor essentially pays a subsidy to the FI to provide preferential lending conditions to a buyer for the purchase of certain equipment.

Advantages and disadvantages of approach for each party

This approach is similar to the FI financing approach, but the coordination between the vendor and FI changes the cost-benefit analysis for each party.

Provided the needed equipment is covered under the scheme, the buyer gains from receiving discounted financing at no additional cost. The buyer may also benefit from the signalling effect that the FI is choosing to cooperate formally with the vendor in vetting potential vendors, reducing information asymmetries and vendor selection costs (the FI de facto provides a “seal of approval”). Buyers may choose to buy higher quality or more efficient equipment as a result of the discount.

The financial institution gains a competitive advantage by being able to provide preferential financing to the buyer at no significant additional financial cost (due to the subsidy received from the vendor). The formal cooperation with the vendor may also result in clients being referred to the FI, expansion into a new sector, or opportunities for joint marketing—all expanding the FI client base. The primary cost to the FI comes from the time and effort required to establish and negotiate a formal partnership with a vendor. There is not necessarily any increase in credit risk as the FI underwrites and approves credit similarly to the traditional FI financing approach.

|

PROS |

CONS |

|

|

Vendor |

|

|

|

Buyer |

|

|

|

SME |

|

|

The primary cost of the approach is borne by the vendor, who must pay the subsidy to the FI upfront or over time. The vendor presumably does this with the goal of increasing sales and winning new buyers. The cooperation with the FI makes the vendor more competitive and encourages buyers with less liquidity to avail themselves of FI financing, also reducing the need for the vendor to provide credit itself. Note that the vendor must also go through the process of negotiating and establishing a formal partnership with the FI. However, going through this process may also provide some benefits in terms of better financing terms from the FI to the vendor.

Key considerations

The successful implementation of a vendor subsidy scheme is particularly dependent on the following three aspects, which should all be considered in detail prior to the implementation of such a scheme.

The FI and vendor must negotiate and come to a detailed agreement that covers all particulars of the vendor subsidy scheme. The agreement should include, but not be limited to:

- a description of the scheme as well as the respective procedures and process flows

- a clear definition of specific equipment and machinery eligible for financing under the scheme

- mutual obligations and responsibilities of both parties

- a timetable for cooperation, including the validity of the subsidy

- financial and promotional obligations of both parties (including the amount of subsidy)

The equipment and machinery to be covered by the subsidy need to be clearly defined, with clear definitions as to what may be included (e.g., parts, maintenance, warranties, options, etc.) The vendor may benefit from limiting the number of products promoted by the subsidy.

Both the FI and vendor need to promote and announce the preferential financing options among their own target groups using specific marketing approaches. Coordination should be established to ensure consistent messaging and a targeted approach to potential clients.

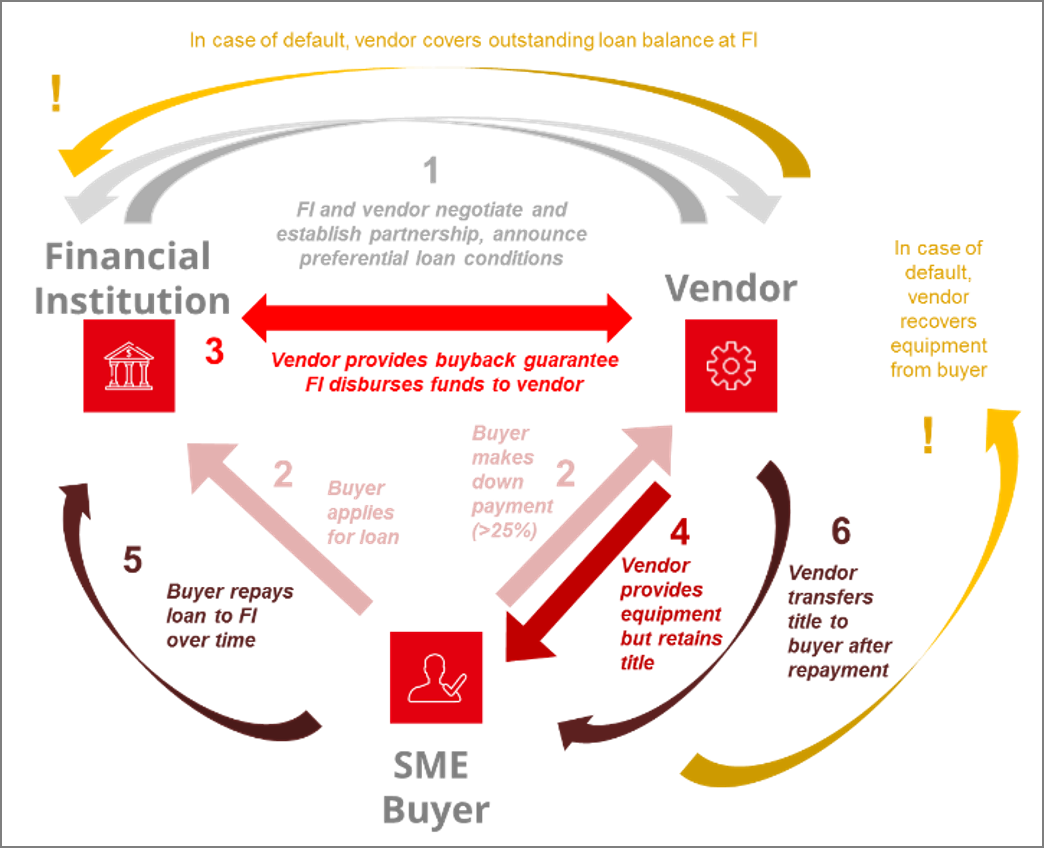

Vendor finance approach #2: buyback schemes

Under the scheme, in order to meet the needs of buyers of its equipment, the vendor agrees to a buyback agreement, i.e., the vendor agrees to repurchase the equipment at a stated price within a specified period of time if the buyer defaults.

The buyback agreement serves as a guarantee to the FI, as the vendor guarantees that it will pay back the buyer’s obligation to the FI, covering the risk of default and thus enabling the FI to provide preferential loan conditions to the SME buyer. The reduction of credit risk resulting from the replacement of the SME buyer’s credit risk with the vendor’s credit risk enables preferential conditions. For example, the financial institution may provide a lower interest rate, a loan without collateral, or an expedited assessment and approval process. The exact specifications of the benefit must be negotiated and defined by the FI and vendor.

In order to enjoy preferential loan conditions, the buyer must make a down payment (typically at least 25% of the total sales price). The purpose of the down payment is to cover the vendor’s risk of having to re-sell the product, as well as to offset any possible depreciation and repair costs. The buyer’s financial participation through the down payment ensures that the buyer remains engaged in loan repayment.

The equipment title will stay with the vendor at the time of sale and until the buyer has repaid the loan to the FI, enabling the vendor to easily “buy back” the equipment if default occurs. Once the buyer has fully repaid the FI loan, the title is transferred from the vendor to the client and the buyback arrangement ceases.

In order to reduce the risk of the buyer damaging the equipment or engaging in inappropriate maintenance or repair, in situations where equipment insurance in unavailable or not feasible, a maintenance agreement is often included in the sale and a maintenance fee to the vendor is included in the cost of the loan from the FI (thus increasing the total transaction amount). This fee covers the cost of equipment repair and maintenance over the lifetime of the loan (while the vendor retains the title)—and represents additional revenue for the vendor.

Advantages and disadvantages of approach for each party

Provided the needed equipment is covered under the cooperation scheme, the SME buyer gains from receiving preferential financing. However, in order to take advantage of this, the buyer must make a down payment upfront and be willing to accept that the transaction amount will include a maintenance fee. Additionally, the buyer will also only receive the actual ownership title from the vendor once the loan has been repaid to the FI.

|

PROS |

CONS |

|

|

Vendor |

|

|

|

Buyer |

|

|

|

SME |

|

|

The financial institution gains a competitive advantage by being able to provide preferential financing to the buyer at no significant additional financial cost (due to the buyback guarantee provided by the vendor). Additionally, the buyer’s credit risk is largely substituted by the risk of the vendor making good on its buyback guarantee, which may reduce credit risk to the bank.[1]

It is hoped that the formal cooperation with the vendor will also result in client referrals, expansion into a new sector, and/or opportunities for joint marketing—all expanding the client base.

The primary cost to the FI comes from the time and effort needed to analyse and assess the vendor, establish and negotiate a formal partnership with the vendor, which must be carefully negotiated to ensure “default” and “buyback” conditions are unambiguous. Analyzing vendors before engaging in cooperation schemes is important to ensure that vendors are able to buy back equipment if and when needed.

The primary cost of the approach is borne by the vendor, who takes on the risk of having to buy back used equipment from the buyer in case of default. While the maintenance agreement helps to mitigate the risk that the equipment is impaired, the vendor bears the risk that reselling the equipment proves difficult or impossible. As a result, care must be taken to ensure the equipment identified for the scheme can be uninstalled and repossessed relatively easily, the liquid market resale value of the equipment is relatively stable, the vendor has experience in reselling such used equipment, and auxiliary costs (e.g., installation costs) are limited.

The vendor provides the buyback guarantee with the goals of increasing sales and winning new buyers. The cooperation with the FI makes the vendor more competitive and encourages buyers with less liquidity to avail themselves of bank financing. The buyback guarantee approach also reduces the need for the vendor to provide credit directly to buyers.

Key considerations

The successful implementation of a buyback agreement scheme is particularly dependent on the following aspects, which should all be considered in detail prior to the implementation of such a scheme.FI and vendor

The FI and vendor must negotiate and come to a detailed formal agreement that covers all particulars of the buyback agreement scheme. The agreement should include, but not be limited to:

- a description of the buyback agreement as well as the respective procedures and process flow

- a clear definition of what constitutes a “default” and what triggers a “buyback”

- a clear definition of specific equipment eligible for inclusion under the specific scheme

- mutual obligations and responsibilities of both parties

- a timetable for cooperation

- financial and promotional obligations of both parties

One of the most important preconditions for the success of a buyback agreement scheme is the vendor’s experience in selling second-hand equipment or machinery. The FI has to make sure that the vendor will be able to buy back respective equipment if and when needed. The equipment and machinery covered by the scheme must be clearly defined and limited to those items the vendor has experience with on the second-hand market. Additionally, clear explanations as to what may be included under the scheme must be considered (e.g., parts, maintenance, warranties, options, etc.)

Both the FI and vendor need to promote and announce the preferential loans covered by the buyback agreement among their own target groups using specific marketing approaches. Coordination should be established to ensure consistent messaging and a targeted approach to potential clients.

Due to a lack of experience in this area, insurance companies in many markets do not insure industrial equipment/machinery. The introduction of insurance could provide an alternative solution to the problem of the misuse and/or damage of purchased equipment. In cases where insurance in unavailable, the contractual obligation for potential buyers to seek service/maintenance only from the vendor and the inclusion of a service fee in the loan amount helps to reduce the risk of misuse or damage to the equipment. g down payment amounts

The down payment amount in a buyback scheme serves to assist the vendor in the case that equipment needs to be “bought back” (repossessed) and resold, assisting to cover repair and depreciation costs. The required down payment amount should be calibrated to ensure it is high enough to compensate the vendor for the risk equipment must quickly be “bought back” but also not too high as to make the offer unattractive to buyers, particularly those with liquidity challenges. As a result, the minimum down payment requirement should be carefully set based on buyer demand, market competition, equipment depreciation and resale value, loan amount and tenor, and the vendor’s experience in the second-hand market.

[1] Vendors, with which FIs have buyback agreements, are subject to monitoring and assessment in line with risk management policies of respective financial institutions.

Some definitions

Segmentation refers to the process of grouping individuals – in our case clients/prospective clients - into groups (segments) with common needs, common behavioural patterns and similar reactions to marketing measures. The point is to identify groups that are homogenous as group or segment and respond in a similar manner to certain offers/situations, but are clearly distinguishable from other groups, their needs and their behavioural patterns.

Correspondingly, a client segment refers to a homogenous group of clients with similar needs and similar behavioral patterns.

The purpose of (client-) segmentation

The key reason for market- or client-segmentation rests in the fact that having identified such homogenous groups allows to better design products, sales channels, and marketing approach for respective groups. It also allows for more effective risk management. This allows to reach out to groups more efficiently and effectively.

- Improved focus: fine-tune products specifically to customer needs, target advertising and marketing and focus on most promising (profitable) subsets of clients

- Competitiveness and client retention: knowing who your customers are and what they want opens the door for pursuing them in a targeted manner and for optimizing pricing of products, tailoring products and services to specific subsets and, in this way, also enhance client loyalty

- Potential expansion: knowing your customers and potential customers, their needs and value for you allows you to expand your business with existing clients and to tap into new parts of the market most efficiently and effectively

- Pricing optimization: When you know the financial situation and social status of your clients as well as risk profile and costs on your side, you can optimize pricing to ensure that customers get the most value for their money and you generate maximum possible revenue

If we transfer this into the world of financial service provision, it means that it becomes possible to more adequately define and control risk by designing methodology, processes and procedures for specific parts of the market as well as designing products to fit better to the needs of specific types of clients. This also entails how best to set up operations in terms of organizational structure and personnel requirements, so that effective segmentation allows you to optimize how you do business in principle.

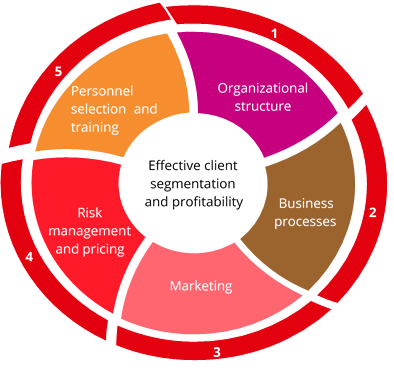

Graph 1: Effective client segmentation as basis for optimizing business

Ideally, client segmentation will result in an optimized strategy, organizational structure, staffing, business processes and product range as the entire approach, product offer, etc. can be tailored to fit the specifics of respective segments. In practice, this usually means trying to make processes, etc. as lean as possible (but as elaborate as necessary) for a respective segment, tailoring product parameters and conditions to meet the needs and possibilities of typical clients of a certain segment and designing your marketing approach and measures in a targeted manner.

Experience teaches, that many enterprises and financial institutions only start looking into segmentation when they start coming under pressure – be it to lower costs due to increasing salaries, continue to be viable in a market with decreasing margins due to increasing competition, etc. One outcome of this is that many businesses, including financial institutions, underestimate the need for collecting, storing and analysing data on clients. In a wide-open and profitable market, it just seems ‘unnecessary’, ‘a waste of time’ on s.th. no-one needs … This comes to haunt businesses and financial institutions later on.

Data used for segmentation

Below we summarize typical data used for segmentation:

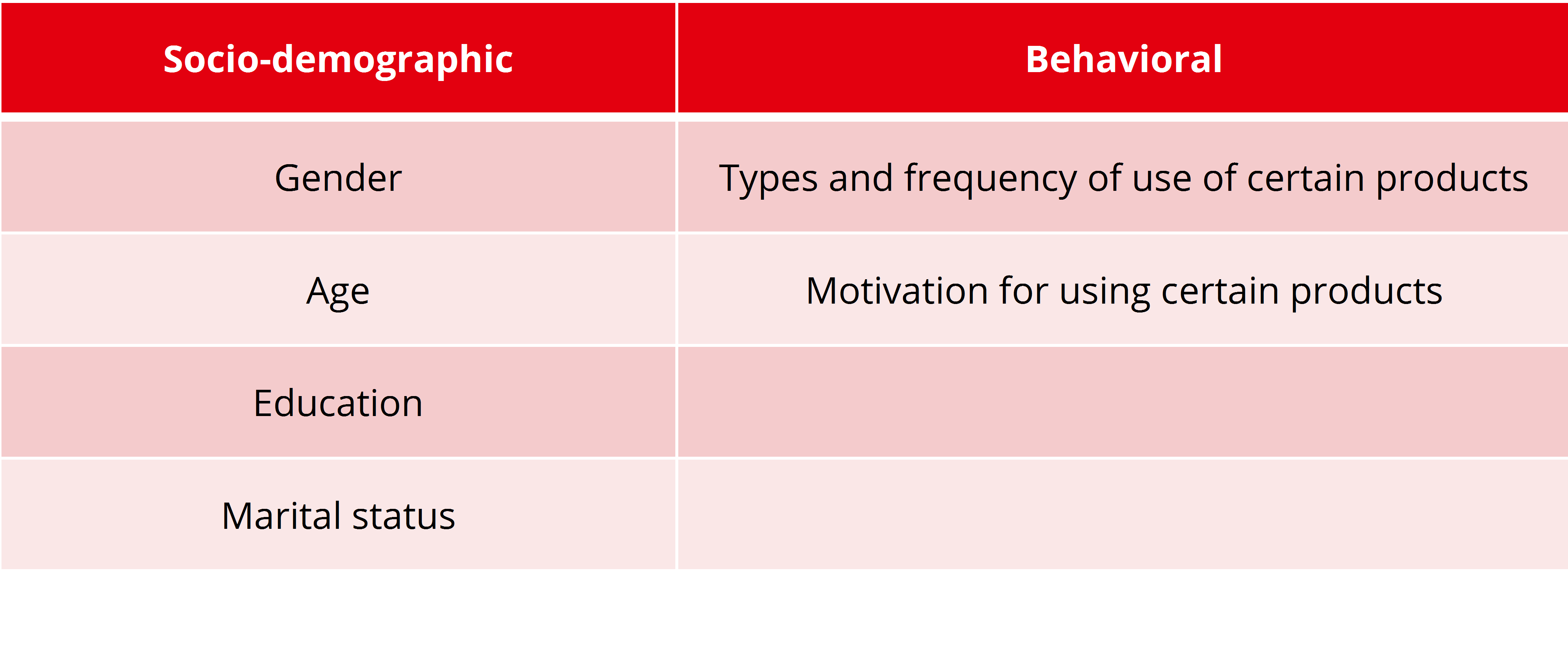

- Socio-demographic information – e.g. gender, age, familial and marital status, income, education, social status, and occupation

- Geographical information – this could be country, region, city, town, county or city district a client resides at

- Psychographics – e.g. attitudes, lifestyle

- Behavioral data - e.g. spending and consumption habits, use of products/services or benefits the client is looking for in products/services

Segmentation approach

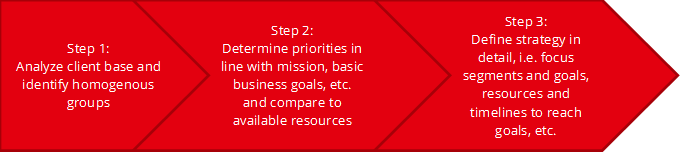

Usually, it takes three basic steps. The basis for meaningfully segmenting an existing or potential client base is information. Only if you have information on who is out there, how they behave, what they need, what they prefer and what they definitely do not need or want, can you start sorting clients into groups.

Based on this, you can then determine where your priorities are, which parts of the market, which clients are of interest to you (generate most value or have the potential for generating value) and what it would take to acquire, serve and retain these clients. You then compare this to your resources, your current set-up, available products, systems, personnel, etc., your strategic goals and plans. This then serves for determining your strategy.

Once you have decided your strategy, you can then go into details on how best to convert this strategy into concrete actions.

Graph 2: Using client segmentation as part of defining strategy

Instruments and data availability

Typical instruments used for analysing markets and client groups are quantitative and qualitative research. This usually takes the form of representative surveys and/or focus groups. Usually, there are professional companies which can assist with this work. In addition, financial institutions can also analyse their own portfolios – if data is available on client profiles, etc. In practice, however, it is exactly this lack of data availability which is a big issue at financial institutions. As indicated above, many financial institutions underestimate the importance of tracking and storing client information, so that, quite frequently, data of a sufficient quality and quantity is not available. Under these circumstances some segmentation is usually still possible but typically less exact, less detailed and, consequently, less useful than would be possible with better data. In any case, all segmentation needs regular review and fine-tuning over time as markets and clients, respectively, client needs and behaviour, may change over time. In any case, it is advisable for financial institutions to track and store client information as completely, correctly and in as much detail as reasonably possible.

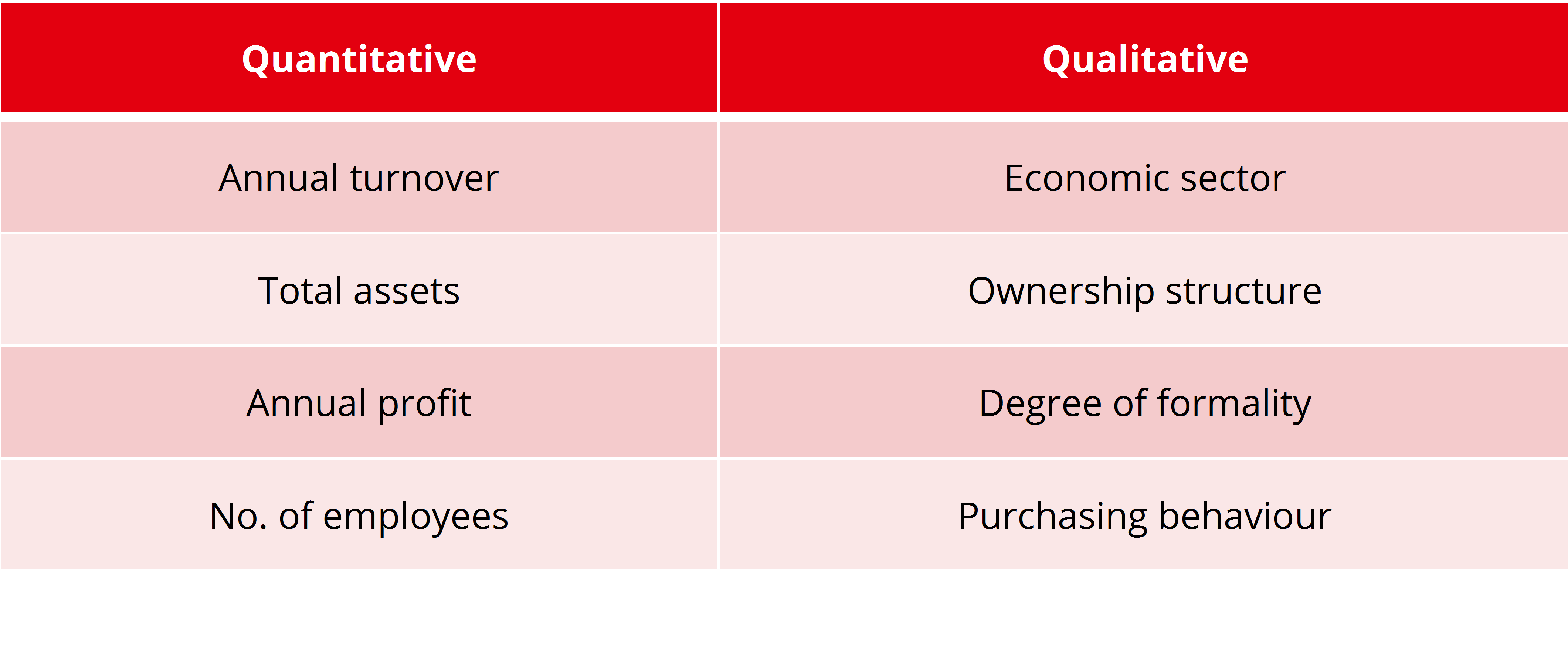

Data can be analysed quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitative approaches typically include looking for clearly distinctive indicators to separate groups from one another and for indicators that help to put certain clients into the same group. In more technical terms, this involves looking for connections between data such as correlations between variables and probabilities that if indicator A applies, indicator B will also apply with a certain probability. Typical examples would be to look for a connection between annual turnover and loan amounts requested or annual turnover and annual profit. Please, note that this in itself says nothing about causality, all it says is that if A changes in a certain way then B is also likely to also change or be different.

Typical indicators used by FIs

When it comes to segmenting business clients, typical indicators used, can include:

Quantitative indicators can usually help at early stages to roughly separate existing client bases or break down a market, but usually just basic quantitative indicators are insufficient to arrive at meaningful segmentation. Take two businesses, for example, with the same annual turnover, the same profit and the same number of employees. However, the one business operates as limited liability company, whereas the other one is set up as sole proprietorship. Clearly, the risk profiles would be different or at least the documents and data you would need from these clients would differ.

Or, to provide another example, take two businesses with the same annual turnover, the same profit and the same number of employees. However, the one business is engaged in housing construction whereas the other is engaged in producing bread. Clearly, the risk profiles differ.

Therefore, usually additional indicators are used to segment clients. In addition to qualitative indicators related directly to the business itself, such as economic sector, ownership structure, etc. there are other factors influencing client behaviour or needs. These can include such indicators as:

In micro lending, for example, generally speaking, data indicates that women tend to be the better borrowers, i.e. more reliable in repaying loans on time than men.

In general, married men tend to be more settled and reliable in fulfilling obligations than bachelors. ‘Older’ people tend to be more responsible than ‘young’ people.

In insurance, for example, women and men often pay differently on car insurance (often there also are different rates for women and men drivers of different ages) as data shows that risk patterns differ depending on gender and age.

So, in short, by analysing your customer base and looking at how different aspects relate to one another you can get a better idea of who your customers are and what they would like to get from working with your institution.

Classification vs. segmentation

Segmentation should not be confused with arbitrary classifications done by governments or other institutions for statistical reasons or to determine eligibility for subsidies or special tax schemes. These classifications are usually quite arbitrarily decided, e.g. to be in line with the definition of other governments, and do not necessarily have their root in any kind of business logic. Consequently, they often are NOT suitable for the purposes of client segmentation.

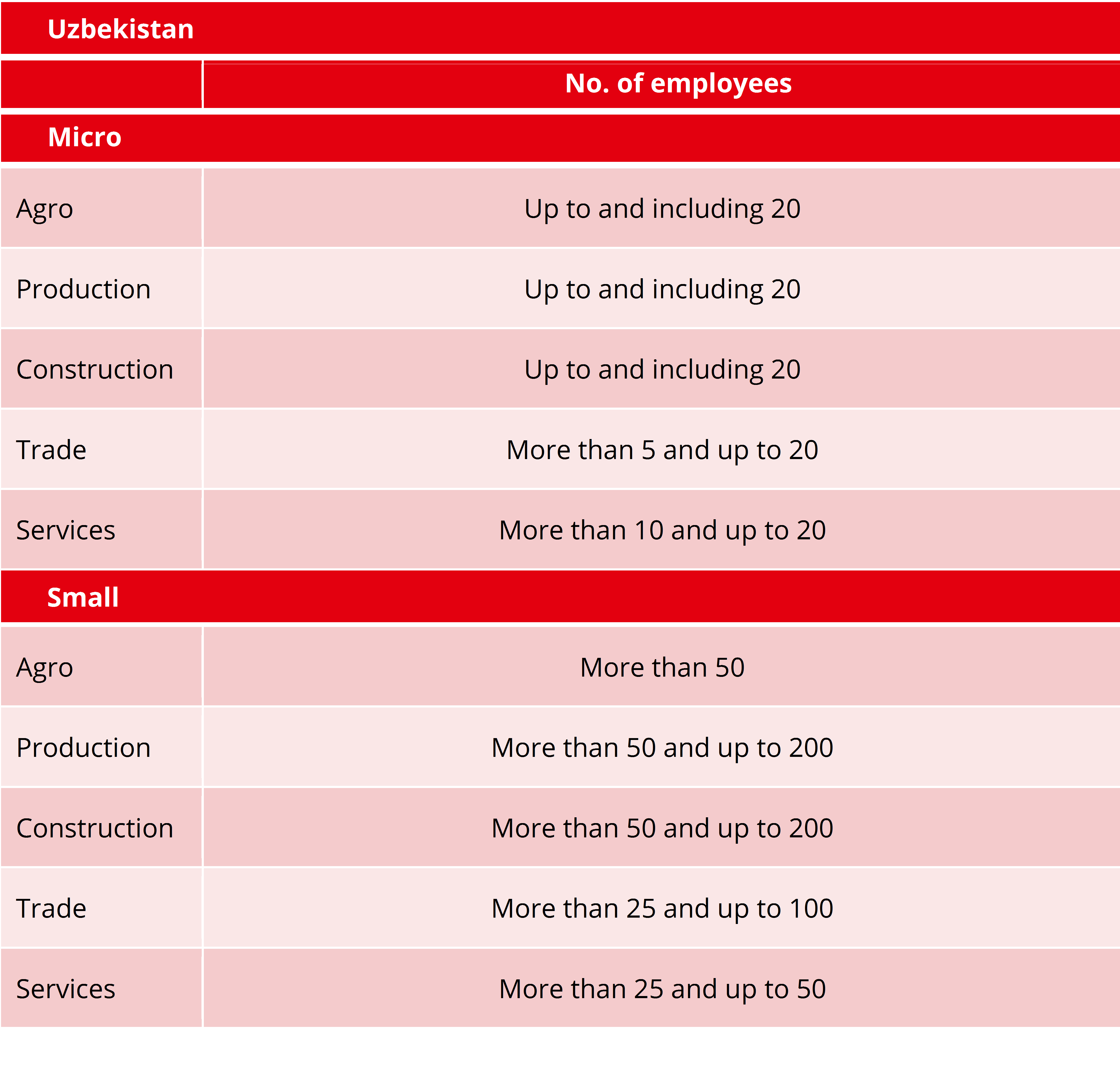

Table 1: Classification of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises in Uzbekistan

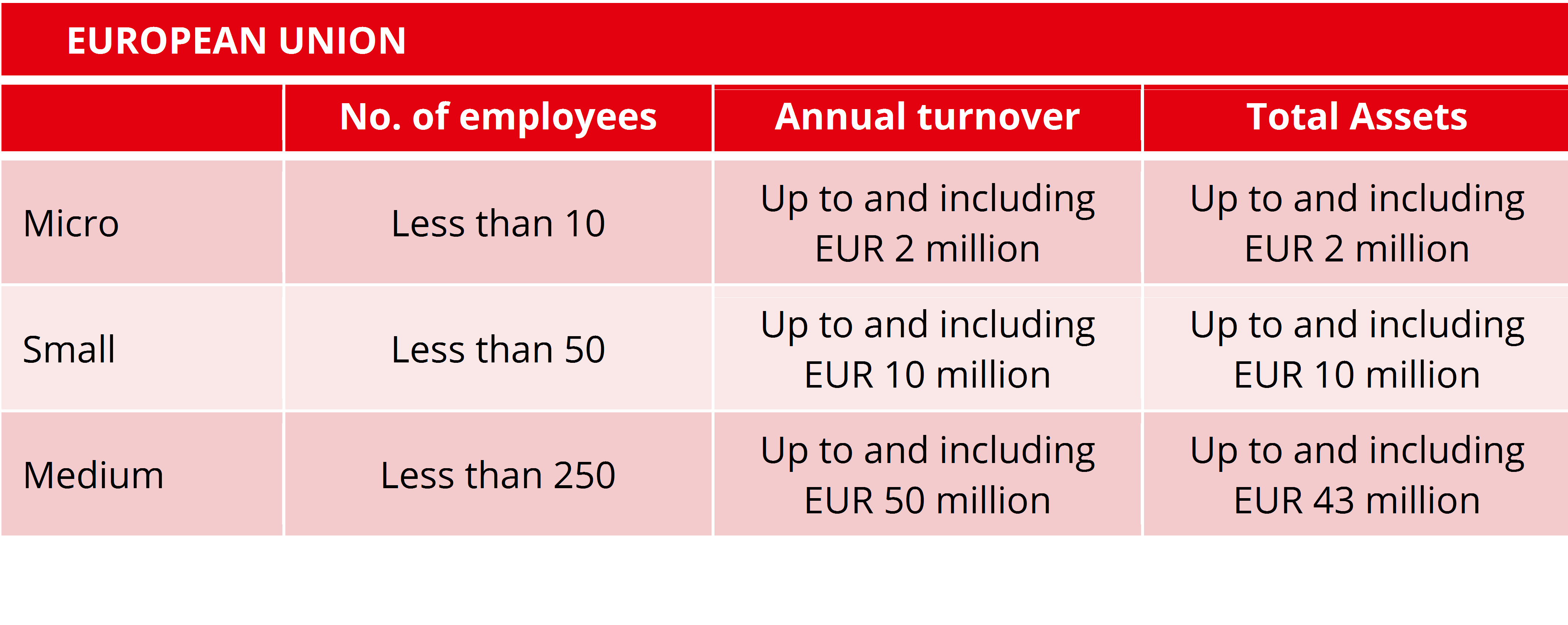

Table 2: Classification of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises in the European Union

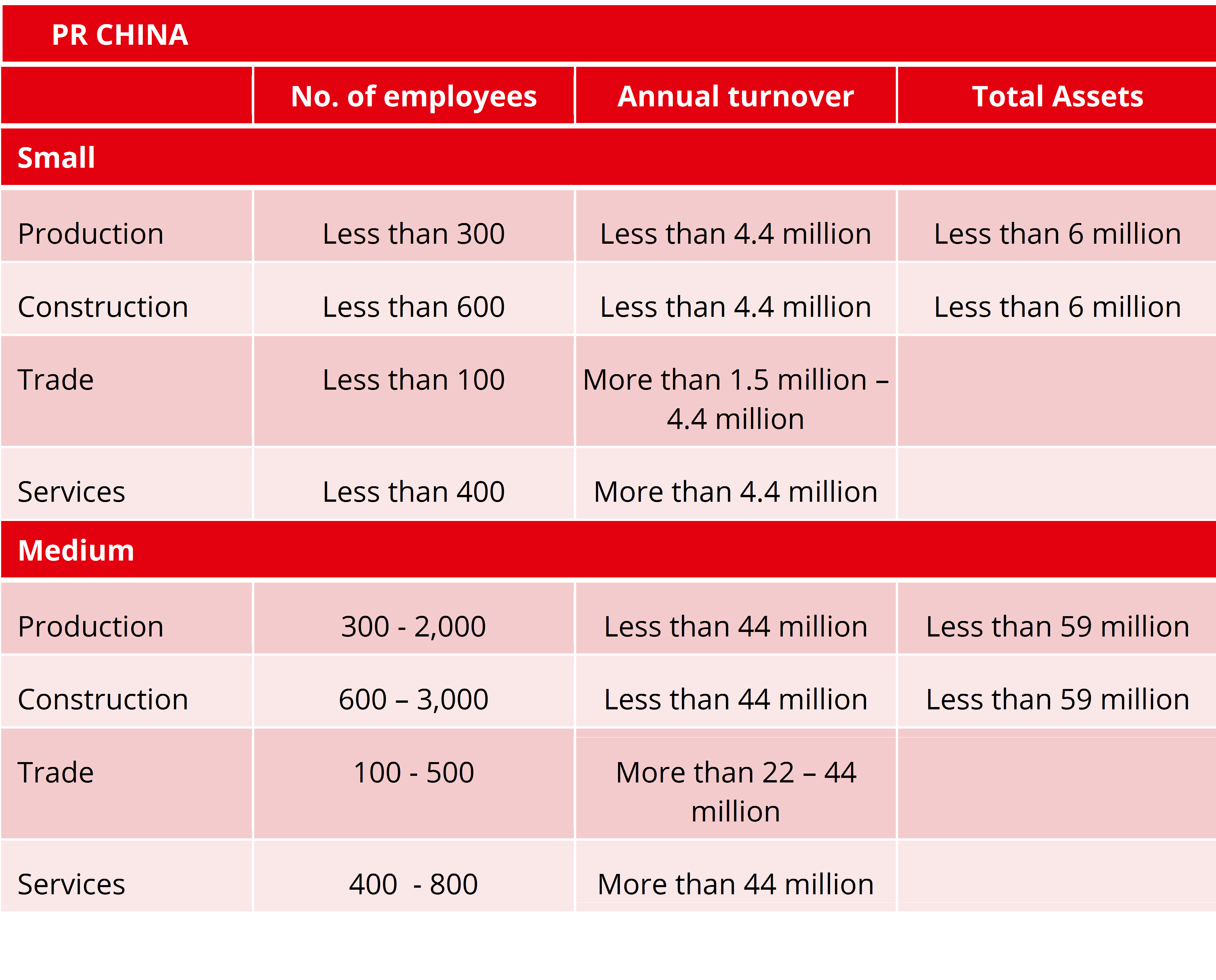

Table 3: Classification of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises in the People’s Republic of China

HOWEVER, CAUTION: typical governmental classification approaches may use what look like the same indicators that you would use for segmentation, such as annual turnover, number of employees, total assets, etc. BUT the actual parameters (values) may be different and the context of how indicators and respective values were chosen is fundamentally different!

Getting your segmentation right

How do you know that your segmentation is working and effective? Very simple – you have succeeded in creating homogenous groups, i.e. groups of clients with a similar profile, similar needs, similar behavioural patterns and – as group - distinct from other groups. The approach and methodology you apply to the respective segment is working in that you are reaching the segment as planned, i.e. you are meeting planned business targets at planned resource investment.

Some final notes

Less is more and simple is usually good! The key is using the right indicators and values. While many, especially new business models, often advertise using a myriad of indicators, quantity in itself does not ensure quality.

Homogeneity allows for standardization and automation! The more homogenous a group, its behaviour and needs, the easier it becomes to focus processes, procedures, products, etc. and standardize them. The more standardized a process, etc. is, the easier it also becomes to automate at least parts of this process.

Segmentation itself requires regular review and adjustment! Just as with other aspects of providing financial services, segmenting clients is not a one-time-shot. Clients change, markets change, needs change, technical possibilities change. Against this background it is clear that current segmentation requires regular review and checking to see if the same indicators and values are still relevant. Another aspect of this is to also check on the emergence of new and more meaningful indicators, respectively, to identify possibly obsolete indicators.

Segmentation is part of a bigger whole! Segmentation serves to help you optimize how you operate your business in all its aspects, i.e. how to best set up operations, define personnel needs, processes, procedures, products, technical needs and infrastructure. It is not a goal or purpose in itself.